World’s most global ICF-accredited coaching school with 40+ years of experience.

The Leadership Assessment that illuminates leader effectiveness

Recognizing, naming, and understanding what our emotions are trying to tell us is life changing. It is a skill as important as linguistic literacy and something we can all learn.

.png)

Clutterbuck Coaching and Mentoring International (CCMI) is a premier training organization specializing in coaching, and mentoring, backed by over 45 years of expertise.

Head Human Potential & Transformation leader, Hero Fincorp | Mentor | Coach | Certified Independent Director

"I recently attended a program to become an ICF certified Coach and Gaurav Arora was our facilitator for the Coaching Program. Gaurav is a very accomplished Coach and a self-aware human being in particular. He brings his authentic self to the program, helps connect the theory with real life, enables a seamless blend in the story of coaching. His ability to captivate attention is outstanding and does a tremendous job for the Erickson Coaching International Program which spreads the word of building his ambition of making India the coaching capital of the world. He doesn't shy away from BHAGs and that's a golden quality. In specific, the drive Gaurav has to make coaching connect with human self-awareness is most infectious part of the program. I wish you Gaurav and Erickson Coaching International India all the success for their future endeavors."

Author at McGraw Hill, SAGE; Advisor to CXO, Board; Principal

"My association with Gaurav began when he interviewed me for his podcast. We met for 20 minutes in person the previous day just to get to know each other and had a spontaneous single take podcast the following afternoon. I was very impressed with the depth and authenticity of his questions, his ability to push boundaries in a conversation so you can become the best version of yourself. It is later that I paid attention to his immense accomplishments as an executive coach. He is equally adventurous in pushing the envelope in embracing technology and experimenting with newer methods to add value to individuals as he is in the art of conversation that ignites, inspires and illuminates. A pleasure to know this accomplished professional"

Chartered FCIPD, Hogan Certified, SPHR, Erickson Coaching International

"A couple of weeks ago, I attended a prestigious program on Coaching (The Art and Science of Coaching) by Erickson International, and having Gaurav Arora as a Master has been an experience I hadn't thought about when I registered for the course.He takes Coaching as a subject to a different level and doesn’t limit it to a Skill but allows exploring oneself and others linking it to the” journey of a Coach, which is the journey of a human being” & 'People are OK'. His unique ability to allow oneself to look within and revisit the different perspectives has been a gift to me. Authentic, and empathetic in his approach provided a safe space to have an open discussion even though the session had only 16 virtual classes. He sticks to a structured approach while teaching different frameworks for coaching but beauty and authority lie in the way he brings them to life with real scenarios making them tangible and relatable. His passion for coaching is infectious and truly gets reflected in his conduct as a Master and Human, enabling others to check the hidden potential all have."

Rich blended journeys that your people will love for making them more productive, effective and happier

Focus on shaping critical leadership behaviors such as emotional intelligence, communication, and resilience, essential for creating a positive and productive organizational culture.

Tailored to build the managerial capabilities of middle managers, empowering them with tools for effective team leadership, strategic thinking, and operational excellence.

Promote gender diversity, empowering women to take on leadership roles and excel in their careers.

Our intentions create our reality. An alignment between our intentions, our thoughts, and our deeds is a source of consistent growth and fulfilling happiness.

Focus on recognizing and nurturing emerging leaders, equipping them with the skills and mindset needed to assume greater responsibilities and contribute to long-term organizational success.

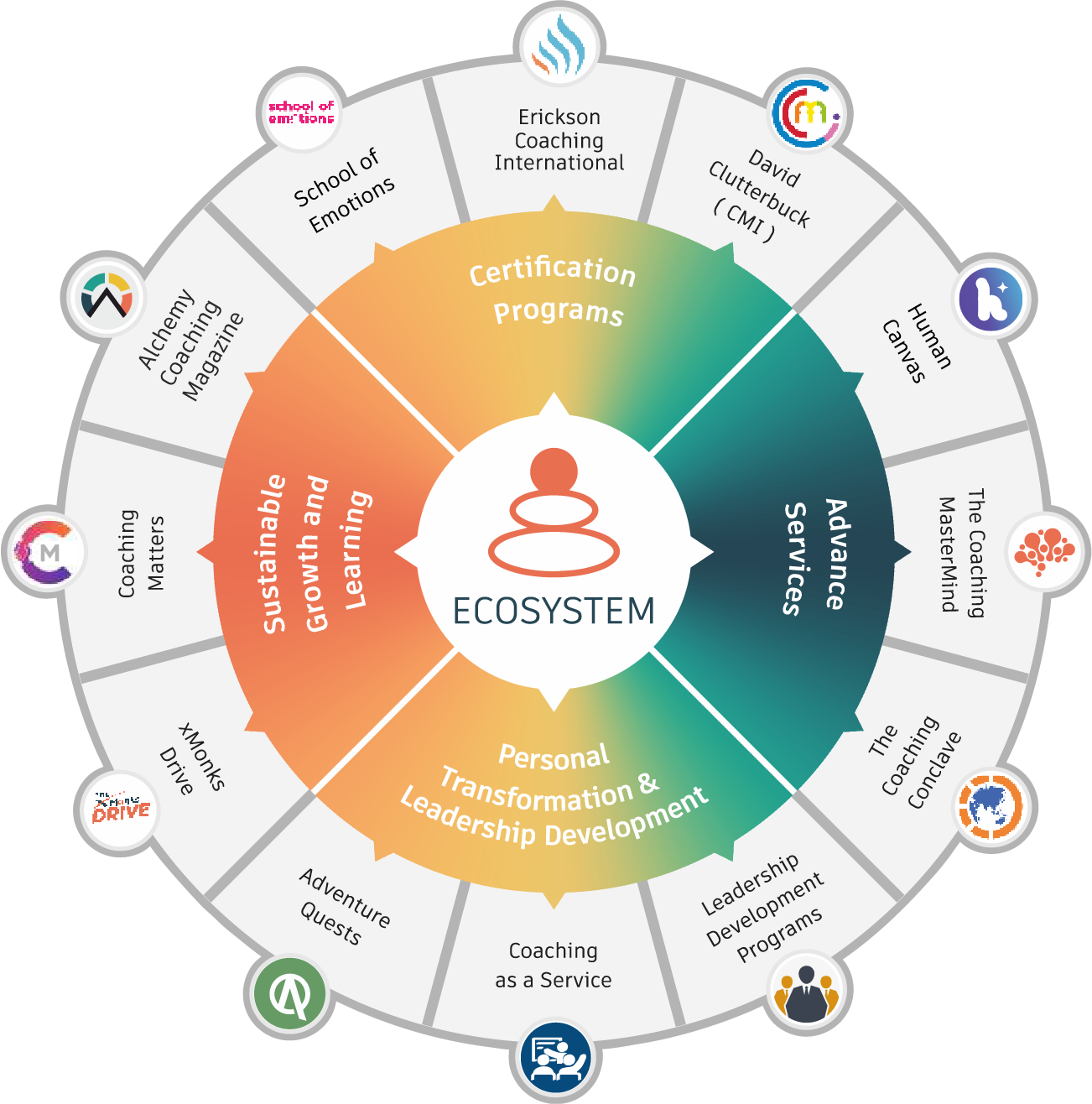

Your Partners To Unlock Your Hidden Potential By Leveraging Our Guiding Principles.

We drive transformation by synchronizing People, Processes and Performance. Our bespoke services in Leadership Development & Executive Coaching empower your team to maximize potential and deliver top performance.

Together We Grow

.png)

Experience top-tier coaching methodologies firsthand in our engaging live webinars

Join Gaurav in candid one-on-one conversations with top-tier leaders, entrepreneurs, C-suite executives, and thought leaders as they share their unique experiences and reflections.

India’s first coaching magazine and a gateway to India's dynamic coaching landscape and our commitment to its growth and ethics. Each quarterly issue delivers carefully curated insights, inspiration, and practical wisdom to support your coaching journey.

Sto sustain learning and growth with our cutting edge technology.

from the world’s leading monks on how to reduce the knowing doing gap.

Discover the power of personal coaching and leadership development. Unlock your potential, embrace clarity, and transform your life today.

Fill in your details below to connect with us.

Explore our latest insights and updates